The Caine Prize for African Writing is back and, as we did last year, we’ll be joining Aaron Bady’s community to discuss what makes the five finalists tick. This year, however, I’ll be taking a close look at each story’s prehistory, from its influences to its allusions. This week’s entry comes from Nigeria: Elnathan John’s “Bayan Layi.”

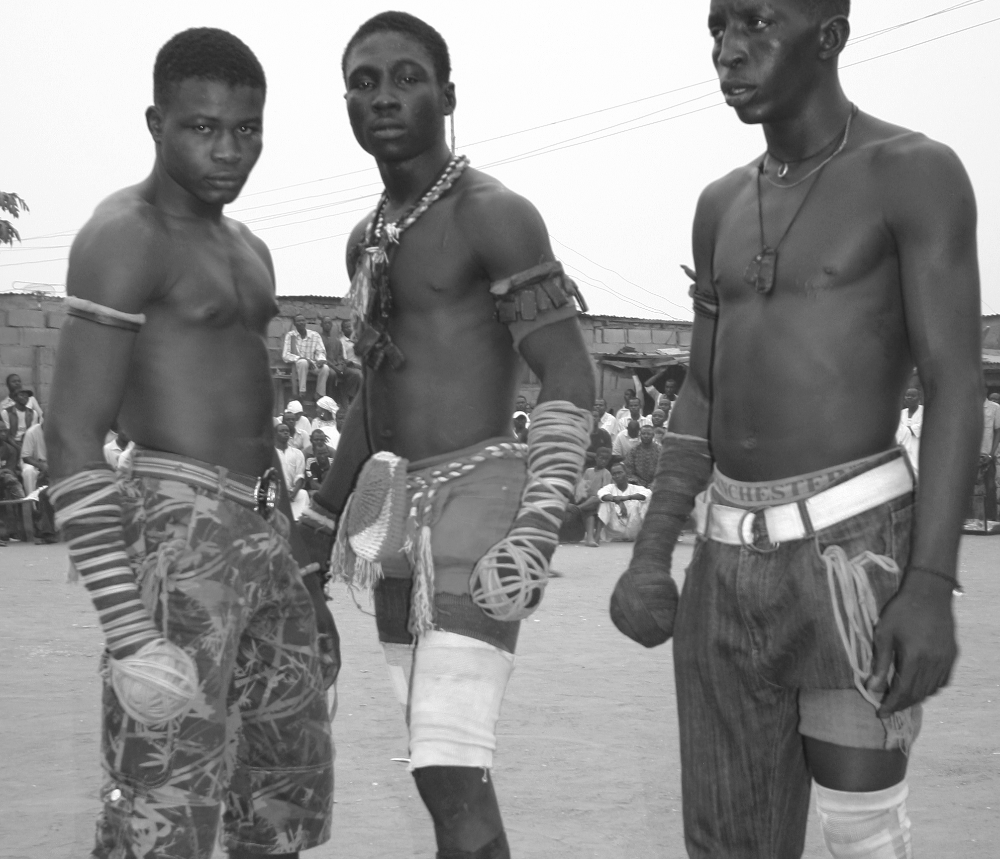

How can religious faith sit comfortably beside the messy horrors of boys fighting to the death? In “Bayan Layi,” this contradiction in terms is reconciled only when the boys that fight put all their faith in Allah. “See how Allah does His things,” the boy telling the story insists. “We didn’t even beat him too much. We have beaten people worse, wallahi, and they didn’t die. But Allah chooses who lives and who dies. Not me. Not us.”

Children can, at times, be incredibly cruel, and symbols of unexpected filth and impurity are everywhere: “White [cloth] is hard to keep clean, soap is expensive and the water in the river will make it brown even when you wash it clean.” In this region of Africa, where Islam is the predominant religion, even intensive Quranic studies can do little to prevent the narrator and his fellow Bayan Layians from becoming agents of violence.

Elnathan John’s story, which has a distinct whiff of Lord of the Flies (or even The Hunger Games), adroitly dances across the line dividing the divine from the human: Boys kill each other, political parties bribe locals to help stuff ballots, and “when someone dies, well, that is Allah’s will.” It is possible to accept this strange stance because it is filtered through the simplistic language of a young boy — young enough not to have a mustache, but old enough to burn a man alive.

Does the story’s childlike voice succeed in implicating its readers? NoViolet Bulawayo brought a similarly stunted, hyperkinetic style to We Need New Names (a chapter of which won the Caine Prize some years ago), and the imperfect English forces us to fill in the grammatical blanks. And as we fill in those small blanks, we cannot help but fill in the larger gaps and imagine ourselves in this world where elections are fixed, family is all but gone and violence is less a shock than a sign of things to come.

“Bayan Lani” ends with its narrator running away from the eponymous town, but leaves us unable to run away from the larger questions and problems it poses of violence's many varieties, whether narrative, political, physical or metaphysical.

A Black Balloon Publication ©

A Black Balloon Publication ©